Designing for Heat: Why temperature must be central to the design process

As climate change accelerates, heat is emerging as one of the most pervasive and underestimated threats to urban environments. It affects everything—from public health and energy demand to biodiversity and social equity. Yet despite its significance, temperature is rarely treated as a core design parameter in new developments.

This oversight is particularly acute in small lot housing, where compact urban forms and limited green infrastructure can amplify heat exposure. Understanding both surface and air temperature dynamics is essential for building cities that are not only livable today, but resilient tomorrow.

Why Temperature Matters

Why Temperature Matters

Temperature is more than a weather metric—it’s a proxy for urban performance. It influences:

- 🌡️ Human health: High ambient temperatures increase the risk of heat stress, especially for vulnerable populations such as the elderly, children, and outdoor workers. Built form outcomes, including social housing must ensure that homes impacted by excessive heat are supported with air conditioning, or improved natural ventilation.

- 🏙️ Urban livability: Heat waves and high temperatures reduce outdoor comfort, discourages active transport, and limits the usability of public spaces.

- ⚡ Energy consumption: Cooling demand spikes during heatwaves, straining infrastructure and increasing emissions.

- 🌱 Ecological resilience: Heat affects vegetation health, soil moisture, and biodiversity, particularly in densely built environments.

Despite these impacts, most developments proceed without a clear understanding of how design choices influence thermal conditions.

The Data Gap in Design and Planning

The Data Gap in Design and Planning

Currently, it is uncommon for architects, planners, and developers to assess surface and air temperatures in new projects. This is due to:

- Lack of accessible tools for microclimate simulation.

- Limited integration of climate data into planning and design workflows.

- Absence of regulatory requirements for thermal performance.

The result is a blind spot in urban design—one that leaves communities exposed to avoidable heat risks.

Insights from the National Climate Adaptation Plan

Australia’s National Climate Adaptation Plan (2023) highlights the need for proactive climate resilience across sectors. Key recommendations relevant to temperature analysis include:

- Embedding climate data into decision-making: The plan calls for better use of environmental data to inform planning, design, and infrastructure investment.

- Protecting vulnerable communities: It emphasizes the importance of addressing heat exposure in areas with high social vulnerability.

- Supporting innovation and collaboration: The plan encourages partnerships between government, industry, and researchers to develop new tools and approaches.

These priorities align with the need to incorporate temperature metrics into urban development—especially in small lot housing, where thermal risks are often highest.

The 10 priority hazards identified in the National Climate Risk Assessment

Small Lot Housing: A Heat Risk Multiplier

Throughout Australia a number of new housing innovations continue to be delivered and tested in emerging communities and in suburbs experiencing redevelopment. Some of the more topical housing forms are the 'small lot' housing products which are typically built on 200m to 400m lots and can include terraces, duplexes and detached housing forms.

The thermal performance of small lots is impacted by a range different design considerations which can be tested and optimised through advanced simulation processes. The follow are key matters which relate specifically to heat and small lots.

- 🧱 High site coverage: Small lots often have minimal setbacks and high building-to-land ratios, reducing space for vegetation and increasing impervious surfaces.

- 🪟 Limited cross-ventilation: Narrow floorplates and close proximity to neighbouring structures can restrict airflow, trapping heat.

- 🌳 Reduced tree canopy: Smaller lots typically lack mature trees, which are critical for shading and cooling.

- 🛣️ Hardscape dominance: Driveways, footpaths, and roads contribute to urban heat island effects, especially when built with dark, heat-absorbing materials.

These factors combine to create microclimates that are significantly warmer than surrounding areas. Without temperature analysis, these risks remain invisible until they manifest as discomfort, illness, or strain on supporting infrastructure.

The Role of Simulation and Measurement

To address these challenges, urban designers need tools that can:

- Model surface and air temperature under different design scenarios.

- Quantify the cooling benefits of vegetation, shading, and material choices.

- Evaluate thermal comfort across seasons and times of day.

- Identify hotspots and vulnerable zones within a development.

Such capabilities enable evidence-based design decisions that prioritize health, equity, and resilience.

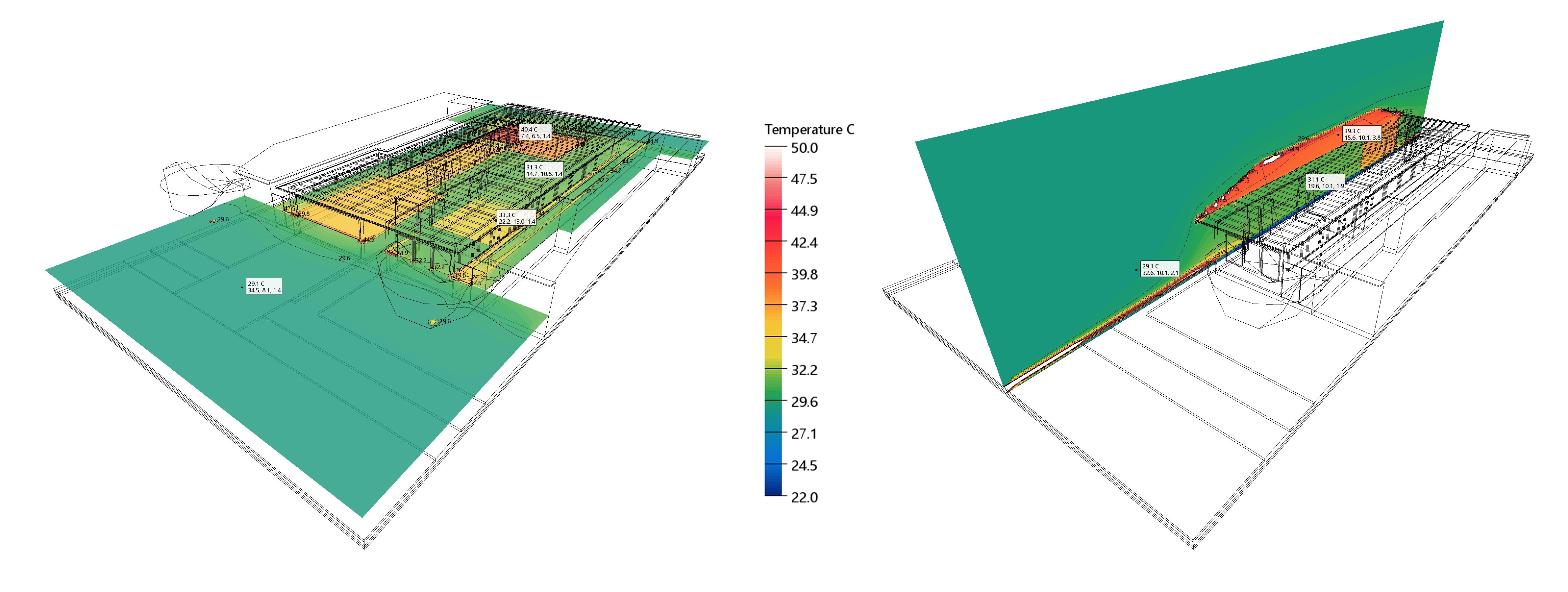

Figure 1: Analysis showing the surface temperature of a small lot home. Both the interior of the building (all rooms and walls) as well as the exterior are determined.  Figure 2: Analysis showing the internal air temperature of the same small lot home. All internal spaces including rooms, ceiling spaces, and windows are considered in the analysis.

Figure 2: Analysis showing the internal air temperature of the same small lot home. All internal spaces including rooms, ceiling spaces, and windows are considered in the analysis.

Urban Vector: Bridging the Gap

At Urban Vector, we specialize in helping architects, landscape architects, planners, engineers and urban designers integrate temperature analysis into their workflows. Our platform and expertise allow professionals to:

- Visualize thermal impacts before construction begins.

- Optimize site layouts for cooling and airflow.

- Assess the performance of materials and vegetation.

- Align projects with climate adaptation goals and policies.

By making temperature visible, we empower design teams to create environments that are cool, comfortable, and future-ready.

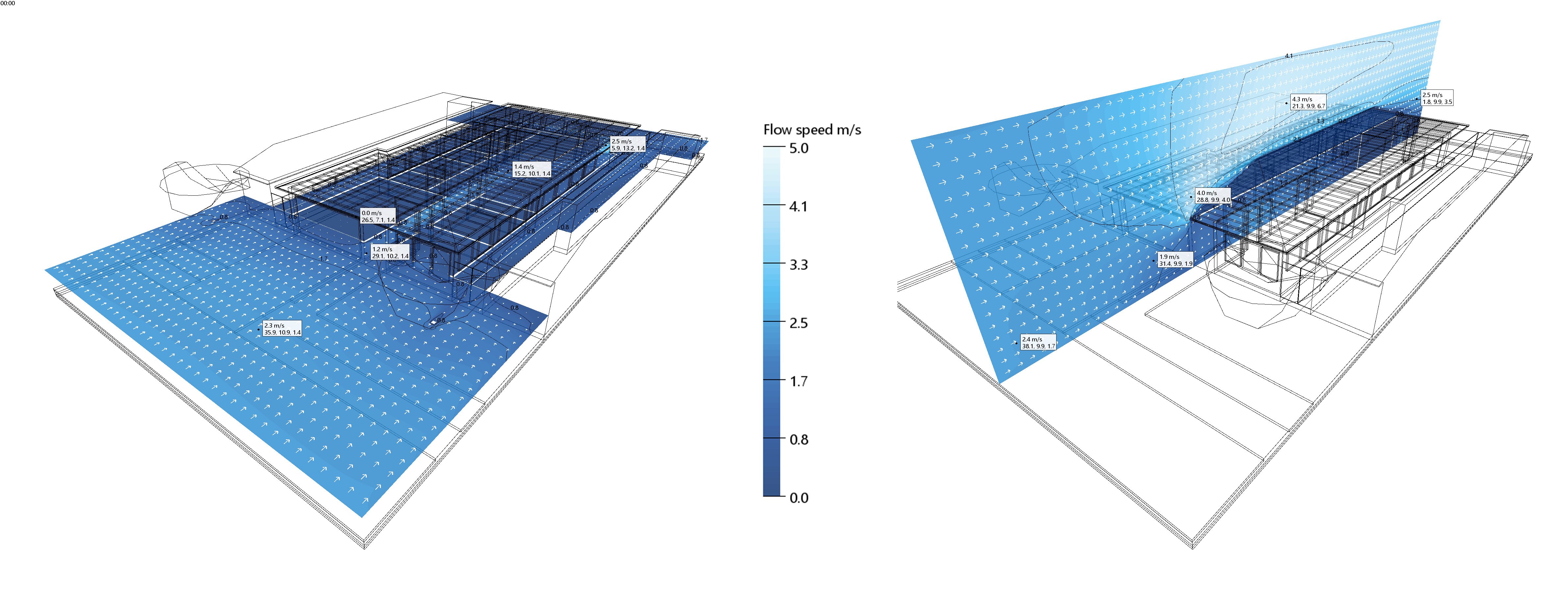

Figure 3: Analysis showing the velocity of breezes around and through the same small lot scenario. The path oof the breeze and the volume of air exchanged with the exterior, significantly reduces the internal temperature of the dwelling.

Toward a Cooler Future

Heat is not just a summer inconvenience—it’s a systemic challenge that demands systemic solutions. As Australia adapts to a warming climate, temperature must become a standard metric in urban planning and design.

With the right tools and mindset, we can build cities that protect people, preserve ecosystems, and perform under pressure. Urban Vector is proud to be part of that mission.

Figure 4: Analysis showing the velocity of breezes around and through the same small lot scenario. The path of the breeze and the volume of air exchanged with the exterior, significantly reduces the internal temperature of the dwelling.

Figure 4: Analysis showing the velocity of breezes around and through the same small lot scenario. The path of the breeze and the volume of air exchanged with the exterior, significantly reduces the internal temperature of the dwelling.