Beyond Compliance: Designing for Comfort in a Warming Climate

Australia’s built environment is at a crossroads. For decades, the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) has provided a consistent framework for assessing the energy efficiency of homes. It has been a vital tool for benchmarking performance, guiding design decisions, and ensuring that new housing stock meets minimum standards for sustainability. Yet as climate change accelerates, the challenges facing our housing sector are no longer just about energy bills or emissions—they are about human health, resilience, and comfort.

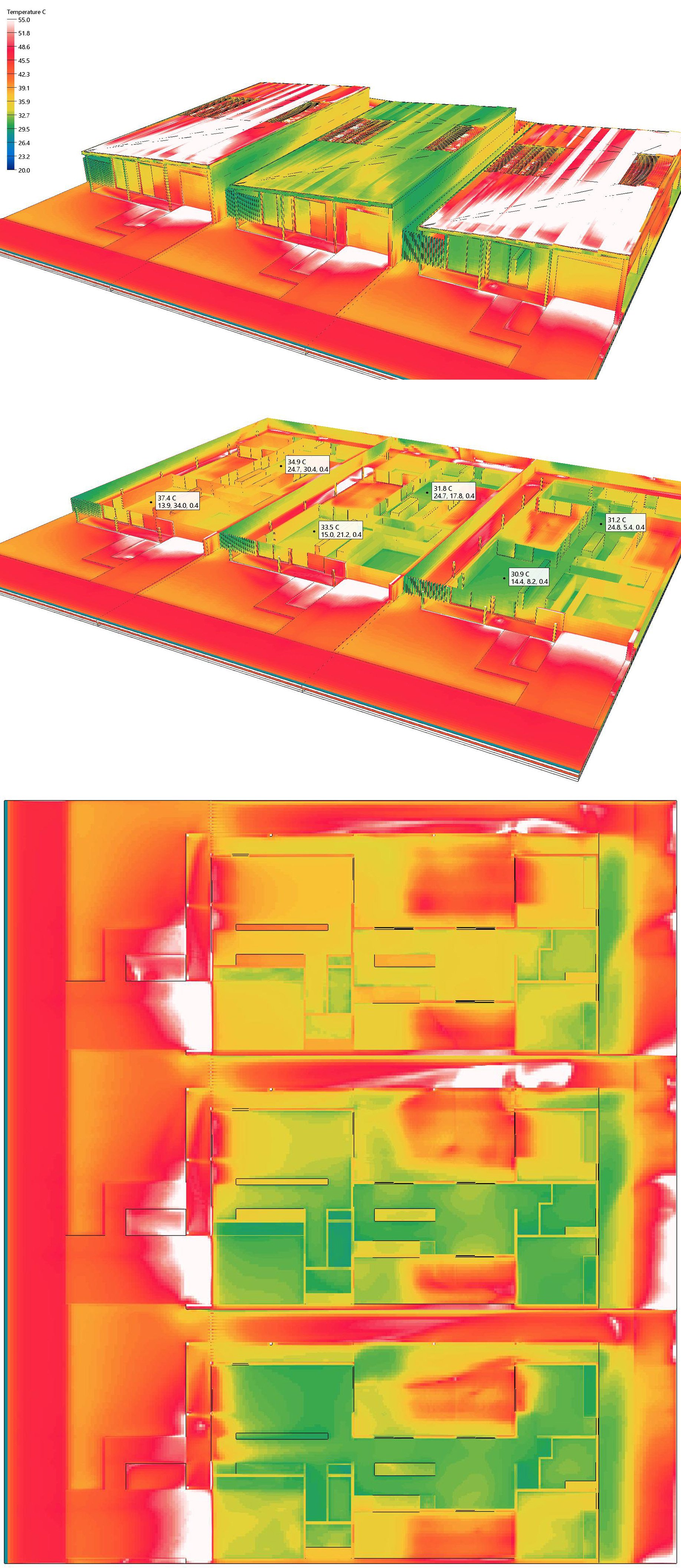

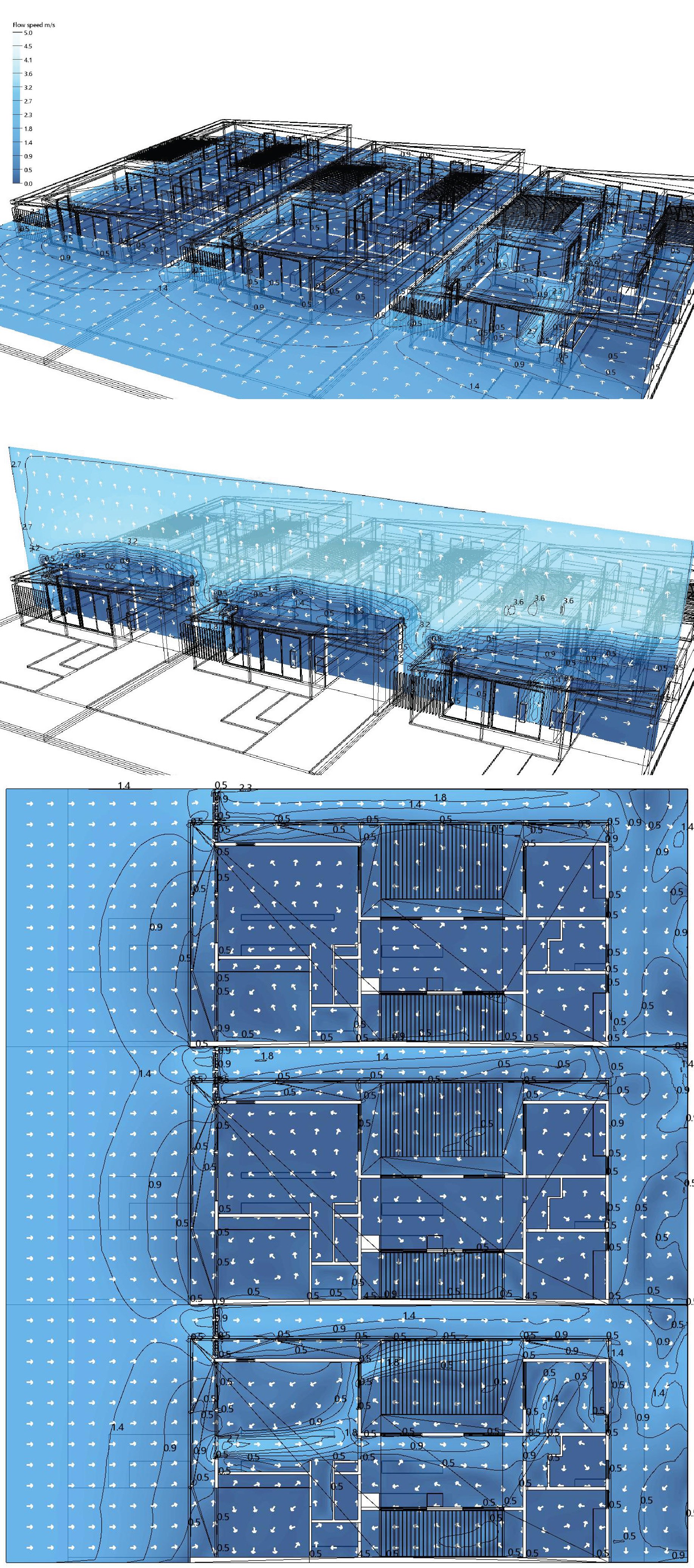

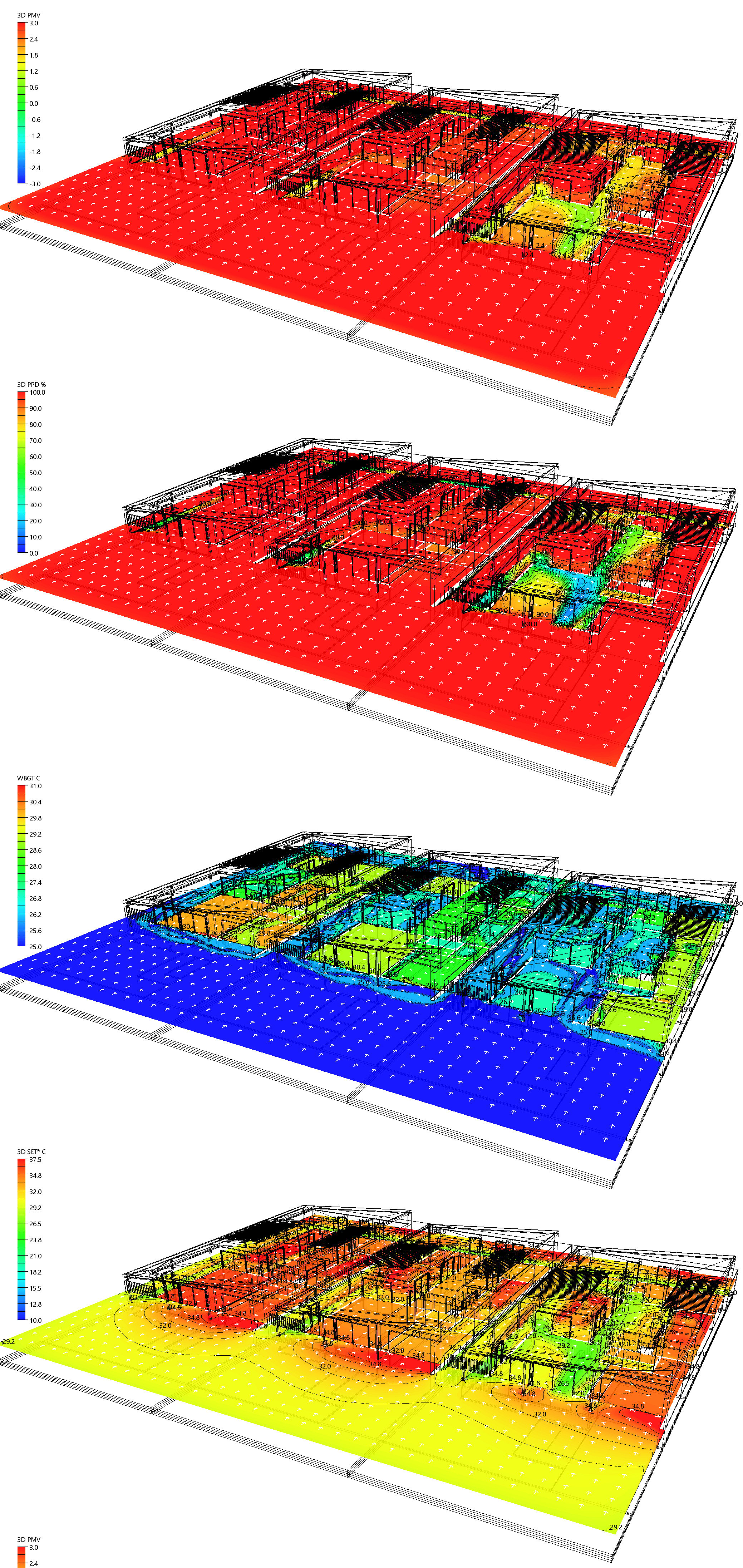

Digital Twin developed by Urban Vector from the plans provided at https://www.yourhome.gov.au/

Digital Twin developed by Urban Vector from the plans provided at https://www.yourhome.gov.au/

This shift is particularly urgent in regions like Far North Queensland, where rising temperatures and humidity are already testing the limits of existing housing. Recent headlines such as “Hot and bothered: Calls grow to address searing Cairns social housing problem” highlight the reality: residents in social housing developments are experiencing dangerous indoor heat levels, with direct consequences for wellbeing. In this context, compliance with energy efficiency ratings is necessary, but not sufficient. We need to move beyond compliance and embrace tools that can simulate, predict, and optimise the lived experience of housing under real climate conditions.

The Role of NatHERS: A Strong Foundation

NatHERS has been a cornerstone of Australia’s housing policy. By providing a star rating system, it allows governments, developers, and homeowners to compare the energy efficiency of different designs. It has helped drive improvements in insulation, glazing, and orientation, and it continues to play a critical role in reducing household energy demand. It has also been supported by the development of multiple climate zone data sets to inform localised analysis.

However, NatHERS is primarily focused on energy consumption. It models how much heating or cooling a home will require to maintain a notional level of comfort, but it does not fully capture the complex interactions of airflow, radiant heat, and humidity that define actual human comfort. Nor does it easily account for microclimatic variations—such as the impact of breezes in coastal towns, or the heat island effect in dense urban areas.

In short, NatHERS provides a strong compliance baseline, but it cannot answer the deeper question: what will it actually feel like to live in this home under real conditions?

Practical Example Assessment

Practical Example Assessment

By way of example, Urban Vector has reviewed many of the designs which have been prepared by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and provided at https://www.yourhome.gov.au/house-designs.

The Brisbane version of the Acacia House has been used to assess the effectiveness of a number of design choices to accurately determine the cost / benefit ratio to the development.

Fluid and Thermal Dynamics

This is where advanced simulation approaches based on fluid and thermal dynamics come into play. These tools allow us to model the movement of air, the transfer of heat, and the performance of materials in extraordinary detail. They can simulate how a breeze flows through a room, how a roof colour affects radiant heat gain, or how humidity interacts with ventilation to influence comfort and address matters like the growth of black mould.

Unlike static rating systems, these simulations are dynamic. They can test multiple scenarios—comparing, for example, the difference between a dark roof and a light roof, or the impact of adding shading devices to a façade. The example below shows three homes with identical physical designs, but with the colour of the roof lightened for one, and simply having the doors and windows opened of another.

Unlike static rating systems, these simulations are dynamic. They can test multiple scenarios—comparing, for example, the difference between a dark roof and a light roof, or the impact of adding shading devices to a façade. The example below shows three homes with identical physical designs, but with the colour of the roof lightened for one, and simply having the doors and windows opened of another.

The simulation is set to determine the performance of structures for 1:00 pm on the 21st of January 2026 with a ambient temperature of 27C, and a relative humidity of 60%. A breeze of 2.4m/s (8.65km/h) is coming from the West. The structures are orientated with their longest dimensions running East / West with the front door and garage access also being located on the West facade. Minimal insulation has been applied to the model to highlight key differences in the materials.

The simulation is set to determine the performance of structures for 1:00 pm on the 21st of January 2026 with a ambient temperature of 27C, and a relative humidity of 60%. A breeze of 2.4m/s (8.65km/h) is coming from the West. The structures are orientated with their longest dimensions running East / West with the front door and garage access also being located on the West facade. Minimal insulation has been applied to the model to highlight key differences in the materials.

Other climatic values are also considered through the use of EPW files (EnergyPlus Weather File Format) including specific solar energy values recorded in a specific geographical location for many years to provide an average for each hour of a year.

https://clima.cbe.berkeley.edu/

https://clima.cbe.berkeley.edu/

This ensures that results reflect the actual conditions of Cairns, Darwin, Sydney, Perth, Adelaide or Hobart rather than a relying on generic climate zone data. For the example above, the Brisbane Airport's EPW file was used to provide the data for the local climate context.

The simulation took approximately 3 hours to complete, and produced a range of results which include detailed internal assessment of energy transfer and the impacts of breezes both within and external to the development.

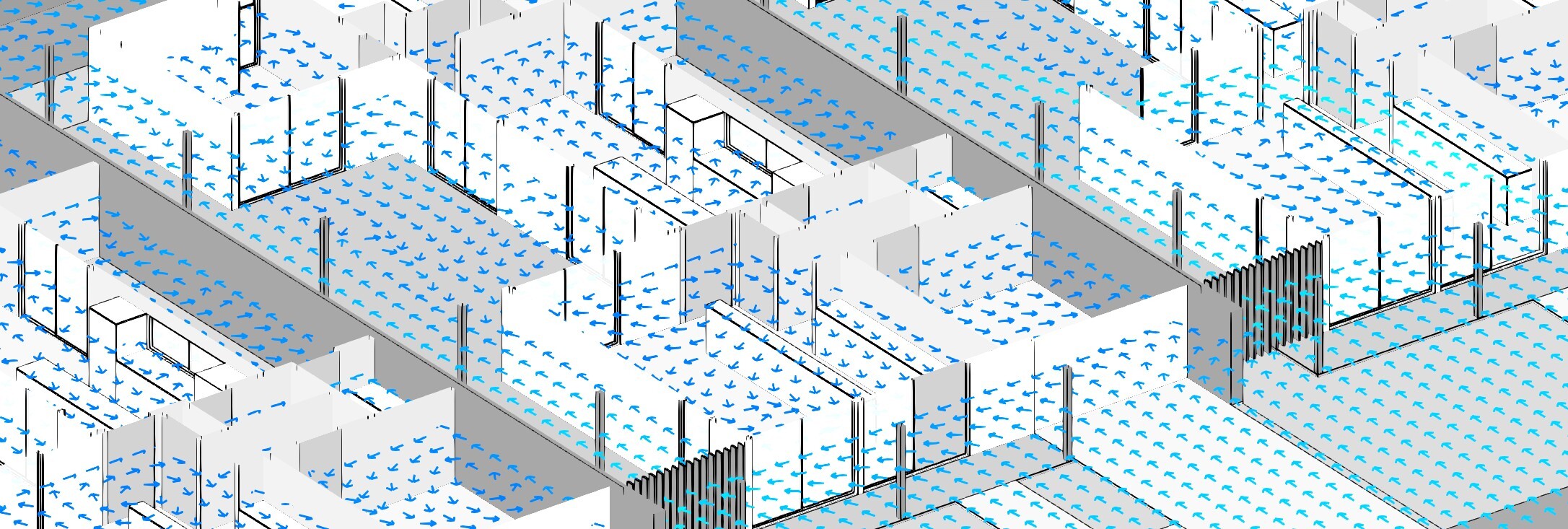

Wind Speed

The simulation shows that the design of the building can facilitate effective cross ventilation through the interiors of the home. The images below show the path of the breeze through the building on the right hand side of the perspective (or at the bottom of the plan view), entering the front door and passing through the lounge and living spaces. The movement of this air volume also assists in improving the speed of wind that passes around the building by channelling flows down the northern part of the block which is setback to the adjacent building.

Naturally, if the site location for this project does not include access to natural ventilation, the positive results shown here would likely not occur. They effectiveness of the design is also based on the orientation of the building with the narrower frontage facing west, which supports thermal reduction through the extended overhang of the roof of this facade.

Air Temperature

The temperature of the structure is influenced by the local climate, design, materials and orientation of built form. The colour of the aluminium roof can clearly be shown to have a significant impact not only on the surface temperature of the roof, but also on the roof cavity and internal living spaces. The heat from the dark rooves can be seen to radiate upwards and downwards significantly impacting the internal temperature of the building.

However, the largest difference to internal air temperature can be achieved by opening windows and doors and allowing fresh air into the structure. This means that the design of each building must consider the size and location of openings to ensure that breezes will pass through the structure. The distance between openings, and the direction of the wind passing through the building is important.

Surface Temperature

Surface Temperature

Whilst the air temperature provides key insights into the performance of spaces and their relative comfort, surface temperature can be used to identify which areas of a design have the highest thermal stress. Looking at the below outputs, it becomes clearer which areas of the homes are retaining heat and which areas benefit most from access to breezes. The lighter coloured roof also has significantly less heat being absorbed on the surface of aluminium.

Humidity, along with heat plays a significant role in determining human comfort. Simulating humidity withing a proposed building can demonstrate how effectively air mixing is occurring either through natural cross ventilation or through the placement of mechanical vents, fans and air conditioning units. Humidity can also provide key insights into how and where black mould may occure within a building. By extending the humidity simulations to include condensation, Urban Vector can determine the optimal orientation of buildings and placements of vans and vents in a proposed architectural design to reduce black mould.

Understanding Comfort

Understanding Comfort

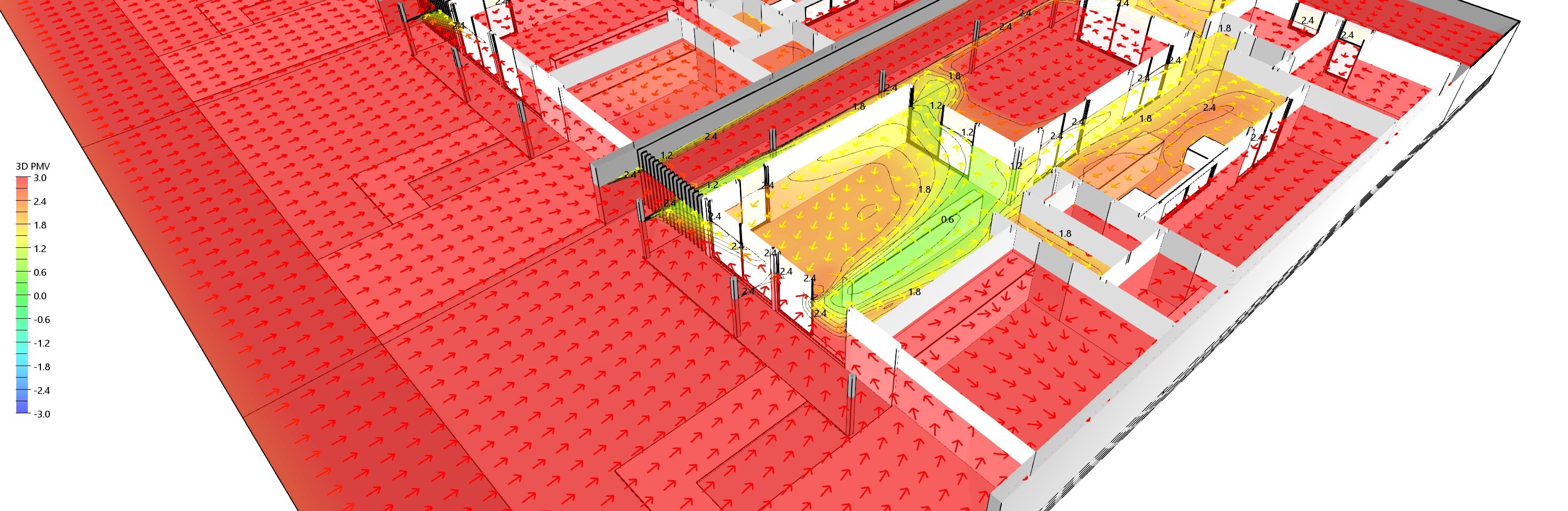

By combining key climatic and design performance data including those outlined above, a system can be established to measure the comfort of humans both within internal spaces as well in exterior settings.

A number of international accreditation standards such as LEED and WELL incorporate comfort requirements from technical standards including ASHRAE 55. Section J of the NCC also relies on these metrics to determine human comfort performance. ASHRAE 55 is used within these systems to evaluate thermal comfort via the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) model. This model helps assess whether indoor environments meet acceptable comfort levels by analysing air temperature, radiant temperature, humidity, air speed, clothing insulation, and metabolic rate. The PMV score ranges from -3 (too cold) to +3 (too hot) with 0 being the key target for internal spaces.

This means that a PMV score can provide a scientifically robust measure of how comfortable (or uncomfortable) a space will be for its occupants. Using the values from a PMV score you can also determine the PPD (Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied) which aims to determine what percentage of any given population will feel satisfied with the comfort levels, noting that some people prefer to be warm vs others who enjoy a cooler setting. This is perfect for Social Housing projects since it focuses on ensuring that the design achieves key outcomes for a broad range of residents based on local climate performance. It can also determine which rooms, or dwellings may not be able to achieve comfort metrics through natural ventilation and determine how much energy is required to cool each room in the project. Two additional metrics have also been included for comparison though it should be noted that WBGT (used by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology) is generally only used in external settings whilst PMV is used for internal calculations.

A Combined Approach: Compliance + Comfort

When NatHERS and advanced simulation are used together, the result is far greater than the sum of their parts. NatHERS ensures that homes meet a consistent national benchmark for energy efficiency. Fluid and thermal dynamics simulations then build on this foundation, validating whether those homes will achieve comfort and resilience under real-world conditions.

For governments, this combined approach offers a powerful decision-making framework. It allows policymakers to set minimum standards while also testing the performance of housing typologies in specific local contexts. It provides evidence for planning controls—such as setbacks, orientation requirements, or roof colour guidelines—that can directly improve comfort outcomes. It also equips councils and state agencies with the data they need to justify climate-responsive housing codes.

Key Analytical Processes

At Urban Vector, we see a clear opportunity to help governments, architects, and planners by offering a range of consulting services aimed at evolving built form designs including:

- Typology Performance Testing

Evaluating how different housing forms—terraces, duplexes, small-lot dwellings—perform under realistic airflow and thermal conditions. This helps identify which typologies are unsuitable for hot, low-breeze regions, and which are best suited to cooler climates.

- Human Comfort Certification

Providing CFD-based comfort assessments aligned with international standards ensures that housing projects are not only energy efficient but also demonstrably healthy and liveable.

- Policy and Planning Guidance

Translating simulation results into actionable planning controls. For example, demonstrating how setbacks or roof colour requirements can reduce indoor temperatures by several degrees, and embedding these insights into local planning schemes.

- Social Housing Design Support

Applying simulations to social housing projects, particularly in heat-stressed regions like Cairns, let us ensure that vulnerable residents are protected from extreme heat, while also reducing reliance on mechanical cooling and saving energy.

Specifically, the following comparative matters can be investigated to determine optimal home design arrangements for key features which, whilst difficult to assess on other analytical platforms, are perfectly suited for testing and validation with human comfort metrics.

Plant species comparison

Plant species comparison

The optimal street tree species should be determine based on leaf area index, canopy density and transpiration rates. Trees should be located in areas which encourage air flow around and through built form features.

Fence type and design

Fence type and design

The type of fencing chosen for a project, should be based on consideration of privacy but also thermal performance. The materials used for fencing and the volume of air that side fences permit around a buliding and through homes can have a substantial impact on the overall design performance.

Glass performance

Glass performance

The thermal performance of various glass types and associated thicknesses can have significant impacts on heat immunity and development costs. Finding the right balance can be determined by simulating the outcomes of each solution.

Surface Colour

Surface Colour

The colour of key materials can have a profound impact on the amount of solar energy which is absorbed vs reflected. To understand the full impact of colour choices, a material's attributes in terms of not only visual light but importantly its near infra-red / or thermal performance.

Roof Types

Roof Types

The type of roofing used throughout Australia is also important in any home energy solution. The difference between roof tiles and metal sheet roofing in terms of thermal performance is significant. With Australia being comprised of many different climate zones, choosing the right roofing for climatic performance but also for cyclone immunity is important.

Roof Form

Roof Form

The placement and arrangement of openings in roofs can have a huge impact on the path of air movement through a structure. The shape of a roof including skillions vs hip designs can also greatly change thermal performance and human comfort.

Why This Matters for Cairns

Cairns is on the frontline of Australia’s climate challenge. With its tropical heat, high humidity, and growing population, the city faces unique pressures in delivering affordable, resilient housing. The recent concerns raised about social housing residents suffering from overheating are a stark reminder that design decisions have direct consequences for health.

By integrating compliance ratings with advanced comfort modelling, governments can ensure that new social housing developments in Cairns are not only affordable and efficient but also safe and comfortable. This means designing homes that stay cooler during heatwaves, that harness natural ventilation, and that reduce the need for costly air conditioning. It also means protecting the most vulnerable members of the community—those who are least able to adapt to extreme heat.

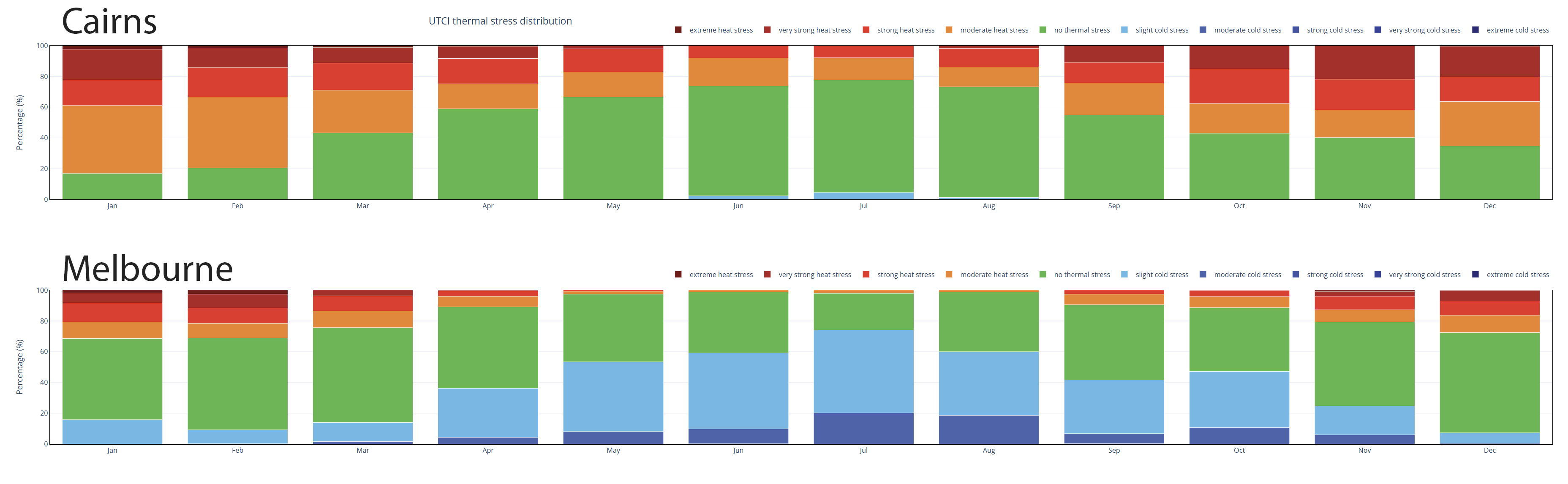

By way of comparison, the following charts show the percentage of time that each location experiences high levels of thermal discomfort. This particular website uses the UTCI (Universal Thermal Comfort Index) human comfort metric to determine the degree of heat risk. As per the below exmample, Melbourne has significantly less heat impacted days than Cairns, however the winter conditions in Melbourne can also create ‘cold stress’.

https://clima.cbe.berkeley.edu/

Ultimately, the goal is not just to meet compliance targets, but to create housing that genuinely improves lives. Engineers, architects, and town planners have a critical role to play in this transition. By embracing advanced simulation tools alongside established rating systems, we can design homes and communities that are resilient, sustainable, and human-centred.

At Urban Vector, we believe this is the future of housing in Australia. It is about moving beyond compliance to deliver comfort. It is about equipping governments with the evidence they need to make informed decisions. And it is about ensuring that every resident—from the suburbs of Sydney to the social housing estates of Cairns—has access to housing that supports their health and wellbeing in a changing climate.

Follow us on #LinkedIn to see design insights and further results from more simulations.